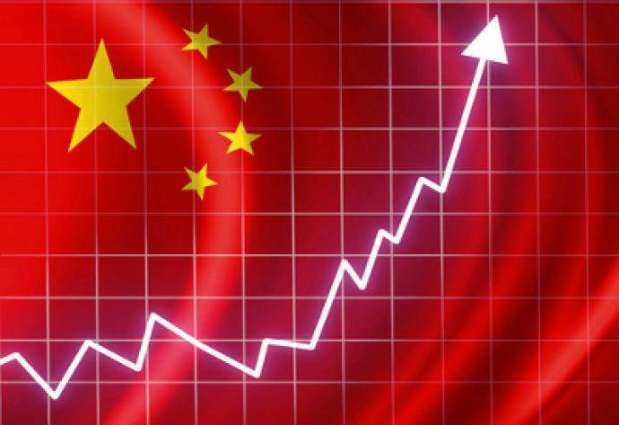

China’s economic expansion after the Cultural Revolution is a result of new capitalist reforms. New political reforms, new trade reforms and new socialist reforms. China had been one of the world’s largest and most advanced economies prior to the nineteenth century. In the 18th century, Adam Smith claimed China had long been one of the richest, that is, one of the most fertile, best cultivated, most industrious, most prosperous and most urbanized countries in the world. Economic reforms introducing market principles began in 1978 and were carried out in two stages. The first stage, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, involved the collectivization of agriculture, the opening up of the country to foreign investment, and permission for entrepreneurs to start businesses. However, most industry remained state-owned. The second stage of reform, in the late 1980s and 1990s, involved the privatization and contracting out of much state-owned industry and the lifting of price controls, protectionist policies, and regulations, although state monopolies in sectors such as banking and petroleum remained. The private sector grew remarkably, accounting for as much as 70 percent of China’s gross domestic product by 2005. The success of China’s economic policies and the manner of their implementation has resulted in immense changes in Chinese society. Large-scale government planning programs alongside market characteristics have greatly decreased poverty, while incomes and income inequality have increased, leading to a backlash led by the New Left. In the academic scene, scholars have debated the reason for the success of the Chinese “dual-track” economy, and have compared them to attempts to reform socialism in the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union; as well as the growth of other developing economies. Capital was definitely scarce at the beginning of the Ten-Year Plan. It was estimated that the Ten-Year Plan goals would cost between $350 billion and $630 billion in 1978 prices. The government had been relying very heavily upon the revenue it gained by requiring the sale of agricultural products to the State at artificially low prices and selling them at a higher price. But this policy did not encourage productivity in agriculture and agricultural development stagnated. The percapita output of grains, as stated previously, was not any higher in 1977 than it was in 1955. The State Enterprises, instead of being a source of profit for the State, required large subsidies necessitating the milking of agriculture.

For the Ten-Year Plan the government sought other sources of revenues. One source it tried to develop was tourism. Hotels and other tourist facilities were built and there was some success, but notably the vast majority of the tourists were overseas Chinese. In desperation China turned to encouraging foreign investment as a way of financing the development projects. German and Japanese companies provided the capital for major projects in return for a share of the benefits. China also reversed its policy concerning foreign loans. In December of 1978 China arranged a $1.2 billion loan from a consortium of British banks and by mid-April China had received or arranged for $10 billion in foreign loans. China in 1978 had a serious shortage of technical personnel. The Cultural Revolution had disrupted the system of higher education for about twelve years. Estimates of the total size of the technical and scientific workforce in China in the 1970’s were in the neighborhood of sixty thousand. For a nation of one billion people sixty thousand is a miniscule amount. By the early 1980’s the scientific and technical workforce had grown to about 400,000, a substantial increase but still a quite small amount for a nation of over one billion people. There is even more of a shortage of middle level technicians and skilled workers. Today Chinese economy became so powerful that they had to intentionally weaken the Juan because his strength as a growing volute threatened the wall street. That is a unique case in history for someone to stop growing of the volute in order to avoid international monetary crash.